World’s Largest Camera

by

Emmett Millbarge

A few years later, George opened a portrait studio in Chicago and educated himself on darkroom technique. Within a few years, he was stablished as a commercial photographer specializing in large-format photography. George loved a challenge and soon adopted the motto, “The Hitherto Impossible in Photography is Our Specialty.” His first major challenge was developing a magnesium compound for indoor photography that generated “more light and less smoke.” The system required flash powder in many locations around a large room, sometimes as many as 350 spots with a single electric charge exploding all of the powder and generating more light and less smoke than previous methods. His accomplishment earned George the nickname “The Father of Flashlight Photography.”

George soon turned his attention to aerial photography and constructed rotating panoramic cameras that were mounted on ladders and towers. This lucrative market included banquets, conventions, legislative sessions and more. It was only a matter of time before the railroad industry would become interested in George Lawrence’s large-format photography.

The Alton Limited was the pride and joy of the Chicago & Alton Railway, and they commissioned Lawrence to make the largest photograph possible of the brand-new train and spent a reported $5,000 to make it happen. In the first decade of the 20th century, that amount was enough to purchase a substantial house. With competion being so intense between railroad companies at the time, the Chicago & Alton Railway figured the money was well-spent. Impressing the public seems to have been the chief motivation for the project.

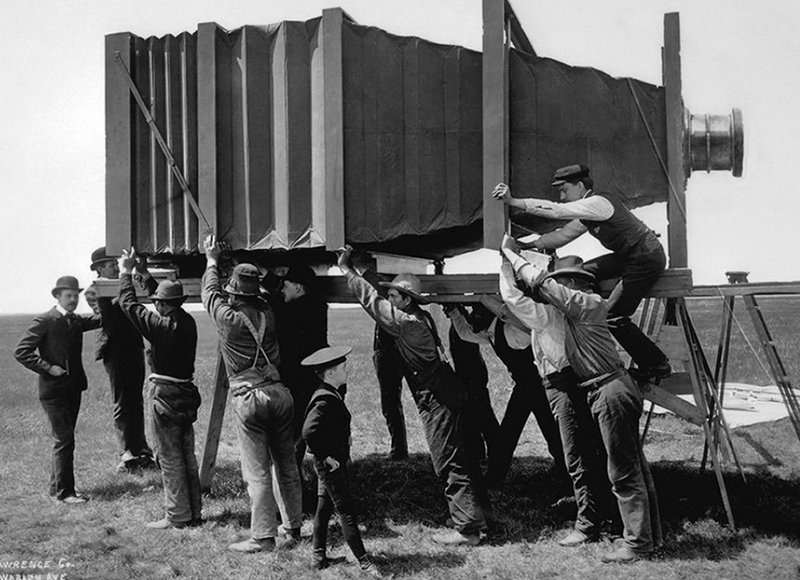

It was on a spring morning in 1900 that a horse-drawn wagon arrived at the workshop of Chicago camera builder J.A. Anderson. The camera he had built for George Lawrence was the world’s largest camera, and it required 15 men to load it into the wagon. The camera was then transfered to the Chicago & Alton Railway Station where it was loaded onto a flat car and moved to Brighton Par, about six miles from the city. Next, the 900-pound camera was carried a quarter of a mile to a suitable location in an open field. Under Lawrence’s supervision, it was set up and pointed at the brand-new train standing in the distance. The images of the train would be made on glass plates measuring 8 feet x 4.5 feet in size using isochromatic emulsion. The glass plate itself weighed about 500 pounds, making the entire camera weigh-in at some 1,400 pounds.

When fully extended, the bed of the camera was about 20 feet long, and the camera had a double-swing front and back. Across the top of the frame at the rear was a small track on which two focusing screens were mounted to move back and forth like sliding doors. Two Zeiss patent lenses were especially made by Bausch and Lomb Optical Company of Rochester, New York. One was a wide-angle lens of 5.5 feet equivalent focus and the second, which was used to make the train photograph, was a telescopic rectilinear lens of 10 feet equivalent focus.

The camera was so large that, prior to an exposure, a man could enter and dust off the glass plate. With the plate holder in position, the large front board was swung open so the operator could pass inside with a camel’s hair duster. Next, the door was closed and a ruby glass cap was placed over the lens and the curtain slide drawn so that the operator could dust the plate in a portable dark room. When dusting was done, he would exit the same way as he entered the camera.

Natural cherry wood was used throughout the camera for the frame and bed. The bellows consisted of three layers: an outer covering of heavy rubber, a lining of black canvas, and an additional lining of opaque black material. Each fold of the bellows was stiffened by a piece of whitewood 1/4 inch thick. The heavy bellows was divided into four sections, and between each section there was a supporting frame mounted on small wheels to move freely on a steel track. The huge plate holder had a cloth-lined wooden roller curtain that was light-tight and could be rolled back to uncover the glass plate prior to the exposure.

On that day, George Lawrence made history with his photograph of the train.

There was a second reason for making the photograph of the train. The railroad company wanted to participate in the Paris Exposition of 1900. Instead of shipping the train to France, the Chicago & Alton Railway decided that the cost of making the huge photograph would be far more economical and the results would be spectacular nevertheless. To accomplish this, three contact prints were made from the perfectly exposed plate and sent to Paris. They were intended for exhibition in the U.S. Government Building, the railway exhibit, and the photographic section.

However, the claim that the photograph had been made from a single glass plate was met with skepticism because no one in Paris had ever heard of a camera capable of making such large plates which were nearly three times as large as the largest plates known at the time. In response, the French Consul in New York was dispatched to Chicago to verify the existence of the camera and to observe its operation. His report satisfied the skeptics in Paris and George Lawrence was awarded the “Grand Prize of the World for Photographic Excellence.”

To accomplish this, he invented a means of flying kites in trains and a way to keep the camera steady under varying wind conditions. He called this invention the “Captive Airship” and used it to produce clear negatives that were 48 inches x 20 inches in size from an altitude as high as 2,000 feet. Lawrence accomplished this using a series of kites attached by short lines that were prevented from being entangled with the main kite line by the use of bamboo spreaders. Depending on the wind velocity and the load to be lifted, he could fly as many as 17 kites in a train.

Examples of George Lawrence’s photography can be found in the Library of Congress. There are photographs of large banquet groups, state legislatures in session, and even the Republican National Conventions of 1904 and 1908, all of which were captured on oversized negatives with remarkable clarity and detail. Also in the collection are large photographs of entire industrial plants in the Midwest.