In 1975, Steven Sasson

by Bill Hedrick

One of the more rewarding aspects of being the editor of this magazine is being able to visit with people who have been a part of the history of our profession. About nine years ago, I visited with a Kodak engineer named Steven Sasson who shared a most fascinating story about a project he was assigned to by Kodak some 46 years ago.

As a child growing up in Brooklyn, New York, Sasson was immediately drawn to electronics and was never one to shy away from exploring new technologies. His innate passion and tenacity are illustrated in this story from his early years. After building an amateur radio at age 13 he accidentally sent out a signal on a banned frequency and received a letter from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC).

“My father simply couldn’t understand how this kid could get in trouble with the federal authorities,” Sasson said in an interview with National Inventors Hall of Fame. “I remember that was the first time that I felt my parents didn’t know what to do with me.” Nevertheless, Sasson’s interest in technology continued to grow, and he attended Brooklyn Technical High School before graduating with both a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Right out of graduate school, he landed a job working at a research laboratory at the Eastman Kodak Company and was amazed that he had found a job doing what he enjoyed most of all: tinkering with electronics. “The most amazing thing about being at Kodak was that they paid me to do what I loved,” Sasson said. “They had all the parts right there, and it was actually a lot easier to do some of this stuff there than it was when I was in Brooklyn.”

At Kodak, Sasson’s supervisor Gareth Lloyd tasked him with finding a practical use for the recently created charged coupled device (CCD) – a mechanism that captures light and transfers into usable data. According to Sasson, the entire conversation took place in a hallway and probably didn’t last 60 seconds. “Hardly anybody knew I was working on this, because it wasn’t that big of a project,” Sasson recalled in an interview with The New York Times. “It wasn’t a secret. It was just a project to keep me from getting into trouble doing something else, I guess.” He had no budget and few specifications.

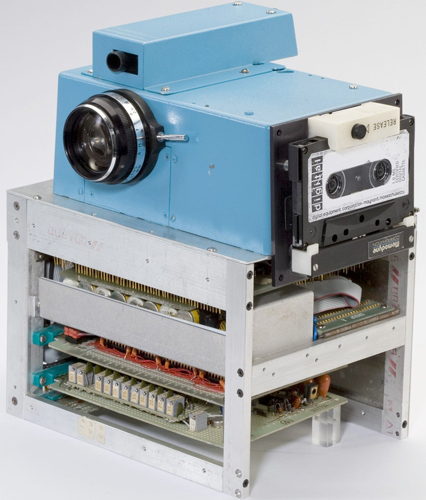

For the next year, Sasson and his small team of technicians would build the very first working model of a hand-held digital camera. It would use solid state electronics, solid state imagers, and the new charged coupled device (CCD) that had been developed by Fairchild Semiconductor just two years earlier. The camera would gather optical information and store it on a removable magnetic tape cassette that could be removed and then played back and viewed on a television screen.

It was a different world in 1975. There were no personal computers and much of the technology we take for granted today simply did not exist. Researchers at Texas Instruments had already filed a patent for a similar idea using analog technology but, as far as anyone can tell, such a device was never built. “Although we had few specifications to meet, I knew that an analog device would not be practical and the size of such a device would be enormous,” Steve recalls. “So, the digital was the only way I knew to do it.”

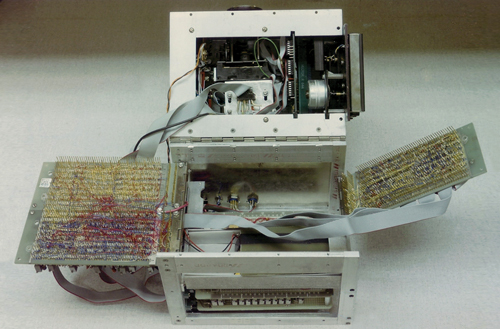

Sasson knew he needed certain components to build this new “filmless” camera. “The actual lens was an 8mm Kodak movie lens borrowed from a junk bin,” he explains. “On the side of the portable contraption was a portable digital cassette instrumentation recorder. There was an analog-to-digital converter that was borrowed from a digital voltmeter application, and several dozen digital and analog circuits wired together on a half dozen circuit boards. The image area consisted of a highly temperamental CCD and it was all powered by 16 nickel cadmium batteries.”

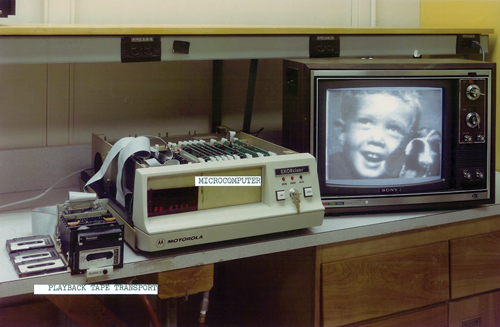

The camera would capture the image using the CCD imager and digitize the image and store it on a standard cassette tape. That process would take about 23 seconds. Next, there had to be a means of playing back the image. “The playback device incorporated a cassette reader and a custom built frame store. The frame store received the data and interpolated the 100 line captured image to 400 lines and generated a standard video signal that could be viewed on a TV screen,” says Sasson.

The “portable” camera itself was about the size of a toaster and weighed in at a little over 8 pounds. The black-and-white image was captured at a resolution of 0.01 megapixels (10K). Not only did it take 23 seconds to record the image onto the cassette, it took another 23 seconds to download the image to the playback system for viewing.

It is interesting to note that, during that year of research and development, Sasson and his team never viewed an image from the device. What they were viewing consisted of test patterns from oscilloscopes and other electronic instruments. However, the day finally came when it was time to take the very first photograph. “I called in a lab assistant named Joy Marshall and took a head and shoulder shot of her,” he explains. But that first black and white image was far from impressive. “Her hair was a silhouette and her face was a blur of static,” he recalls. After some minor adjustments, the image was restored.

It was time to demonstrate the new device to an internal audience at Kodak in 1976. Sasson laughs as he recalls the “insensitive” title he chose for the demonstration title… “Film-Less Photography.” Sasson would photograph one person and lecture for the 23 seconds it took to record the image and move on to another person. When the first image appeared on the TV screen, the questions began pouring in. “Someone wanted to know why anyone would want to view an image on a TV screen. Another asked about storing these images and there were other questions about what an electronic photo album would look like. But the big question was about when such a system would be available to the consumer,” says Sasson.

That was a difficult question to answer back in those days, according to Sasson. In short, the technology necessary for making this a viable option to film just wasn’t there in 1976. “We knew that the future of the digital camera would be based on the evolution of the computer itself,” he explains.

Nevertheless, Kodak saw it as a wave of the future and began quietly, but intensively, researching the concept. “It’s funny to look back on this project and realize that we really weren’t thinking of this as the world’s first digital camera, but rather a distant possibility.”

“You have to understand that Kodak had certain standards to maintain in image reproduction. In 1976, the image produced by this new camera was comparable to 110 film, but not as good,” says Sasson. For Kodak to produce a system for the public that would meet their specifications and standards, technology would have to advance beyond what it was at that time. So, Kodak’s marketing department resisted the experimental device and Sasson was told they “could” sell the camera but they wouldn’t, for fear it would cannibalize film sales. At that time, Kodak made money off of every step of the photography business. Why give that up?

In his technical report on the project, Sasson stated, “The practical implementation of this system requires that a significant amount of progress be made in the areas of charged coupled device (CCD) image sensors, digital memory, integrated circuits and microcomputer technology. The most significant needs are as follows: higher resolution, broader spectral response and increased dynamic range.”

The report goes on to talk about the “camera of the future” by stating, “The camera described in this report represents a first attempt at demonstrating a photographic system which may, with improvements in technology, substantially impact the way pictures will be taken in the future. A future camera for the consumer may be envisioned as a small device capable of taking color pictures under very low light conditions. The pictures will be stored in a magnetic medium on a nonvolatile solid state memory which will be removable from the camera for playback… The picture, existing in electronic form, could be sent over conventional communications channels with little or no modification.”

Obviously, Kodak was headed in the right direction and had a firm understanding of existing technology as well as future developments in technology. As to the question of “when” this technology would replace film capture, Sasson himself predicted about “15 to 20 years.” But, in reality, Kodak was working on this new system and improving upon it as new technology became available. As early as 1991, the Space Shuttle was using a digital camera developed by Kodak. But it would be another ten years before Kodak would begin selling mass-market digital cameras. In the meantime, Kodak was busy obtaining hundreds of patents on digital imaging technology. Practically all digital cameras today rely on these patented inventions. While Kodak’s digital camera patent portfolio earned the company billions of dollars, the company was slow to adopt digital photography and, in 2012, filed for bankruptcy.

For inventing the digital camera, and revolutionizing the way people communicate with each other, President Barack Obama, in 2009, awarded Sasson the National Medal of Technology and Innovation. In 2011, Sasson was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. A year later, the Royal Photographic Society awarded him the prestigious Progress Medal.

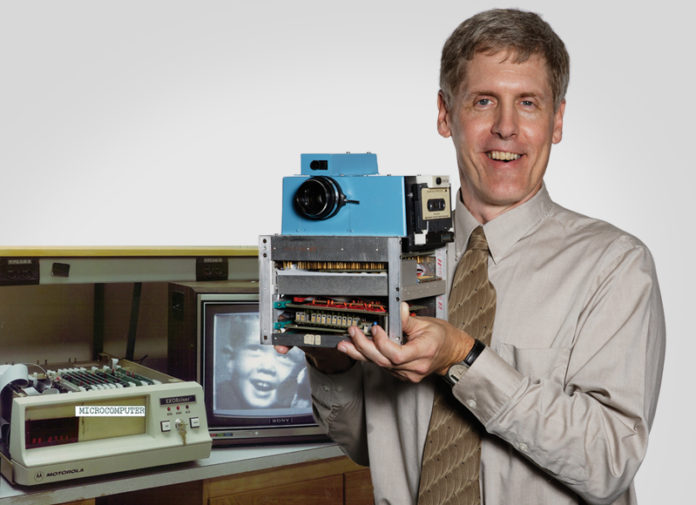

Steve Sasson kept that prototype camera for the next 30 years as he moved throughout the company, mostly as a reminder of this “fun” project. But, outside of the patent that was granted on the concept in 1978, there was no public disclosure until 2001. Today, the first digital camera that Steven Sasson made in 1975 is on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. It’s inventor, Steven Sasson, has now retired from Kodak and dedicates his time to promoting the importance of creativity and inspiring students to improve the world by creating innovative solutions.

Since those pioneering days at the Kodak Research Lab, technology has come a long, long way. Few predicted how fast those sweeping changes would come about and the world of film capture seems little more than a footnote to many photographers today. Digital capture changed the world for professional photographers and technology is advancing faster than anyone ever imagined while we go about our lives taking it all for granted. Steven Sasson and his small team of technicians at Kodak never set out to “change the world” but history tells us that they did just that.