by Joe McDonald

Every photographer has heard the phrase ‘f8 and be there,’ inferring the obvious, you must be present and you must be ready, too. But to really make great wildlife images there is more to it than just that axiom.

Of course you have to ‘be there’ to capture a photo, but for great wildlife photographs being ’there’ may not simply involve a lucky chance encounter but instead may require a lot of time in the field. In today’s world, there is a lot of immediate gratification and, if watching cell phone addicts are any indication, there’s a short attention span too. For great wildlife images, for shots that rise above a mere snapshot or record shot, a great deal of time may be involved. Great shots may have to be earned.

That invested time might simply mean visiting an area repeatedly, going away without results some of the time but always returning in the hope that the next visit will be productive. For most wildlife photographers that’s not a hardship; merely being in the field and enjoying the outdoors is its own reward. And, unless you have a specific subject in mind to the exclusion of anything else, almost any excursion will result in some worthwhile photography.

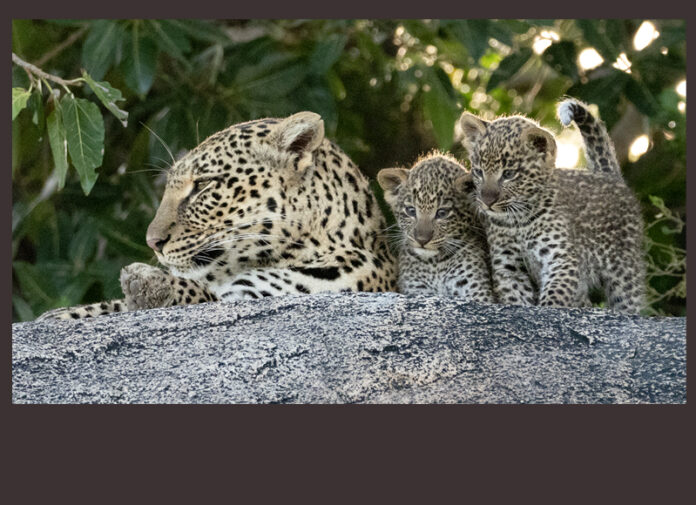

But spending time takes on an entirely different dimension when having patience is involved. Things can be quite different when you have a particular goal, however. Sitting in a photo blind as you stare at a desert waterhole, hoping that a Bobcat or a Javelina family may stop by for a quick drink, or standing in a safari vehicle under a hot sun, waiting and hoping that a mother Leopard will climb out onto a rock with her two cubs, this takes patience. Being there isn’t enough, you have to ‘be there’ for as long as it takes, and sometimes, with the conditions that are involved, you really do feel like you’ve earned the shot!

My wife, Mary Ann, and I have been leading wildlife photo tours and safaris for over thirty years, and we’ve found that our participants generally fit into two categories. Wildlife photographers, especially those who are going on their first photo safari, are either incredibly patient or, to be charitable, fairly impatient. Some novices, not knowing what to expect, may be quite willing to spend hours with a Cheetah or a Leopard, content to watch, photograph, and wait with the hope that something really exciting or interesting may happen. Those folks are a joy to be with, and their patience is often rewarded. Many ‘veteran’ safari-goers are equally patient, as they know from experience that things don’t just happen.

The opposite are those who want everything to happen immediately. They want nature and wildlife to work on their time schedule, not on Nature’s where there is really no schedule at all. Sometimes I think wildlife documentaries are to blame for this impatience as incredible footage and stories require only an hour’s worth of your time. I appreciate that most of the BBC wildlife documentary series end with a segment showing what was involved in filming a particular subject. In almost every case the filming involved a lot of time and effort, sometimes requiring months on site, or returning for two or three years for a couple weeks,

before the photographers finally got the desired shots. Anyone watching those segments would have a better idea of what wildlife photography really requires but unfortunately, not every photographer watches those programs, or appreciates or learns from these behind the scenes stories.

Patience, then, is one of the key ingredients for quality wildlife photography. I’ve found that the longer I’ve been doing this the more patient I’ve become. Sometimes, while on a safari, I’ll be asked if I ever get bored, especially when we’re waiting for an animal to show up, or to wake up, or to do something. Well, of course I get bored, watching a sleeping big cat or a boulder at the lip of a Leopard’s den really isn’t too exciting. But although I’m bored, I’m patient, too, as I know that being ‘there’ may result in our group getting great images. I often answer that question by saying wildlife photography is kind of like playing the lottery. In our state, TV advertisements lure gamblers by saying you gotta play to win. Well, with wildlife photography, you gotta be there to see it happen, and ‘it’ may not happen in a timely fashion.

For most of us, patience alone isn’t enough, unless you have unlimited time. Most of us do not have that luxury, as a typical overseas safari rarely lasts 20 days and a domestic photo vacation often involves just a week or two. In contrast, professional film crews are paid to stay with a subject, day after day, so their job may be to sit on a sleeping lion pride all day. I’m sure they get bored, too, but if something does happen, they’ll be there. Most of us are on tighter schedules, and that’s where another vital ingredient comes into play: knowledge.

Saying that, I’m reminded of a Kenny Roger’s song with the line “You gotta know when to hold ‘em, know when to fold ‘em” when I consider the interplay between these two ingredients, patience and knowledge. While it’s true that anything can happen when you’re dealing with wildlife, most of us have to play the odds whether or not something will happen, and that’s where knowledge of your subject and experience come into play. Sometimes it is worth waiting, and sometimes it is best to move on.

But there are always exceptions. Once, on safari, we left a large pride of well-fed Lions sleeping off their meal of a Zebra or a Gnu because, with full bellies, the likelihood of the Lions hunting again or doing anything of interest was remote. We continued with our photo safari before returning to camp for a mid-day break. That afternoon we drove by our gang of sated Lions to discover that under a hot sun, with bellies filled to bursting, the pride had killed an Eland, the largest and one of the toughest antelopes in Africa. When we left the Lions earlier, there wasn’t any prey in sight, and the Lions certainly looked down for the count. So … you never really know.

Regardless of those painful exceptions, knowing behavior and knowing what an animal is likely to do is invaluable, and something that is only gained via a combination of study and field experience. Participants on safaris and photo tours should expect their photo tour leader to have both, but sadly, in the real world, some ‘leaders’ are less informed than the folks they are leading.

Regardless of subject, chances are if you’re looking at an impressive body of work of a photographer, you can assume that photographer knows his or her subject. Whether that’s beetles or birds, salamanders or seals, the truly great shots often reveal character or intimacy that is possible only by knowing the subject.

In Chile, we were photographing a family of five Pumas at the end of their meal. One by one the younger cats left the kill and wandered off, while the mother rested nearby. When she started moving she called to her cubs as she walked in a different direction. Mary grabbed her gear, asking rhetorically ‘What do cats do after eating?’ They drink, and Mary was heading down the hill to a nearby pond. Our group followed, covering the rocky hillside a bit slower than the Pumas, but we arrived in time to capture the entire family as they drank at the pond’s edge.

Animal behavior is fascinating, and observing wildlife can be just as much fun as the photography. Over the last few years I’ve read several books that dealt with animal intelligence and emotion, where the authors made valid comparisons between what animals might be thinking and how we humans think. We’re not that different. Now, when I’m watching a group of Lions crossing the Serengeti grasslands or a scattered group of Brown Bears on a tidal flat, I’m looking at the animals differently. Now, I consider how I would behave in these conditions rather than how I think the animal should. That, my friends, used to be the big sin of anthropomorphism, imparting human feelings on animals, but more and more scientists are seeing a commonality between ‘them’ and us, and for predicting animal behavior, this thinking has been invaluable.

Here’s an example. While we were watching Brown Bears in coastal Alaska, one young male approached another, walking confidently and, to our eyes, aggressively, while the other bear seemed intimidated and shy. The ‘aggressive’ bear chased the other repeatedly, as if it was driving the other bear away from the rich feeding grounds. Watching all this, I said to our group that the pursuer just wants to play, and seconds later the bear that was being pursued stopped, turned, and faced the other bear as if it finally got tired of being chased. Sure enough, they began to wrestle, and it was obvious that it was just play. I looked like a genius! Of course, anyone watching the bears and who has owned a dog has probably seen something similar when a dog wanted to play.

In writing this, I’m not trying to discourage anyone, implying that you have to be an expert to get great shots. But I am encouraging photographers to get to know their subject. That can be accomplished, often, simply by being patient and watching and observing, letting knowledge seep in, passively but cumulatively. Personal observations may trigger a desire to learn more, where one consults books or websites for more information. As you learn more, new ideas will come to mind, perhaps in compositions or in capturing a particular behavior. As you spend more time with your subject you’ll be seeing more as well, giving you a chance to execute those new ideas and probably germinating new ones. Patience and knowledge, they go hand in hand, and if you apply both, one day, without you even realizing it, you will be something of an authority on the subject! And your photos will show it.

Joe McDonald has been photographing wildlife and nature since he was a high school freshman and was selling his photos to the National Wildlife Federation. He has been published in every natural history publication in the U.S., including Audubon, Bird Watcher’s Digest, Birder’s World, Defenders, Living Bird, Natural History, National and International Wildlife, Ranger Rick, Smithsonian, Wildlife Conservation, and more. He is the author of nine books and one e-book. Joe is especially well known for his expertise in electronic flash and using equipment for high speed flash and for remote, unmanned photography. For more information, go to: www.hoothollow.com

Joe McDonald has been photographing wildlife and nature since he was a high school freshman and was selling his photos to the National Wildlife Federation. He has been published in every natural history publication in the U.S., including Audubon, Bird Watcher’s Digest, Birder’s World, Defenders, Living Bird, Natural History, National and International Wildlife, Ranger Rick, Smithsonian, Wildlife Conservation, and more. He is the author of nine books and one e-book. Joe is especially well known for his expertise in electronic flash and using equipment for high speed flash and for remote, unmanned photography. For more information, go to: www.hoothollow.com