with

Lyne Raff

Photographically speaking, I am from the Dinosaur Age… a time long ago before “ASA” became “ISO” and camera straps had loops for carrying your film rolls. Many changes have taken place since my early days in photography, and the recent buzz on Instagram and other social media is all about images that have a “film look.” Actions for Instagram filters are easily found for Photoshop, and it’s not hard to make your digital images look retro. So, with the ease of digital cameras, why would anyone bother going analog these days?

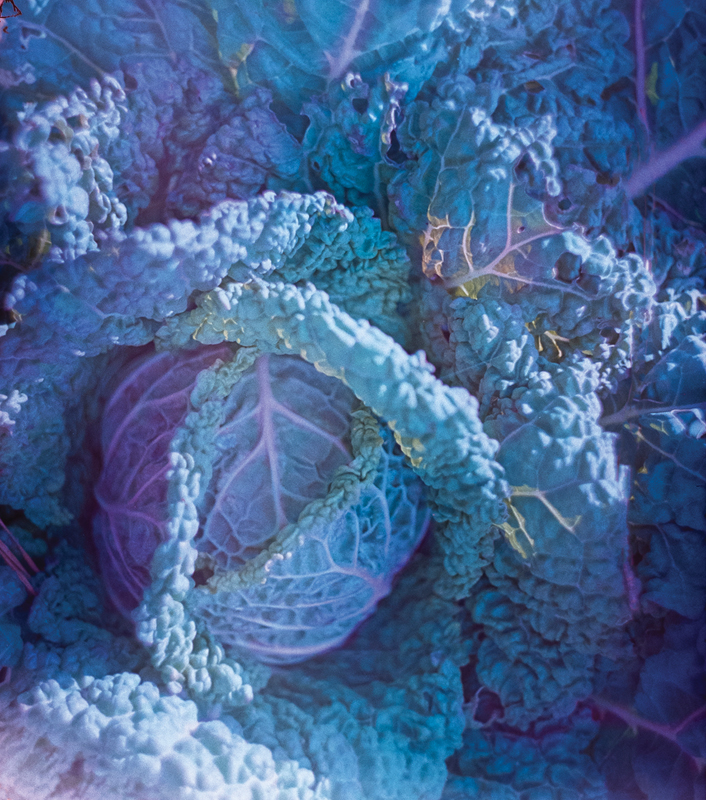

The answer to that question is, “…because film rocks!” Why else would there be so many ways and actions and filters meant to try and digitally duplicate film? Sure, there are things that a digital camera does hands-down better than a film camera (instant image review is the biggie), but film can do some things that digital can’t… amazing color dynamic range, for one.

The answer to that question is, “…because film rocks!” Why else would there be so many ways and actions and filters meant to try and digitally duplicate film? Sure, there are things that a digital camera does hands-down better than a film camera (instant image review is the biggie), but film can do some things that digital can’t… amazing color dynamic range, for one.

In addition, using a film camera, especially a vintage one or antique, gives you a feeling of connection to the past. You can walk in the footsteps of greatness by using the same camera as Diane Arbus (Rolleiflex TLR), Henri Cartier-Bresson (Leica 35mm Rangefinder), Dorothea Lange and Edward Weston (Graflex). That alone is incredibly inspiring!

However, creativity is what film can offer a modern digital shooter more than anything else. There are also huge possibilities with film photography. For example, your images will have a look that is hard to duplicate digitally (if not impossible), and what you end up with depends on three things: the Camera, the Film, and the Unexpected. All those little things that are outside of your control.

Cameras – The camera you select to use will have probably the greatest influence on your images. Each type of camera and different models of cameras within a brand will all have their own ‘look’ to the images they take. Film cameras, especially vintage ones, can be a complete wonder to use, or they can be a strange, mechanical monster! Once you get the hang of working with an analog camera, you will likely find they are a real joy to handle and to use. They just feel different in your hands. The trick, though, is to really understand the relationship between shutter speed, ISO, and aperture (the Exposure Triangle) because a great many vintage analog cameras do not have an Automatic setting!

There are a few paths you can go down with film cameras: rangefinder cameras, pocket-type (point and shoot) cameras, artistic-type cameras, twin-lens-reflex cameras (TLRs), precision cameras, and medium format cameras. The point-and-shoot cameras (35mm, 110, 120 films, and instant films) that are meant to be fool-proof are easy to operate and images can vary. If you are wanting to experiment with snapshot-feel images, these cameras are for you! The list includes Kodak Brownies (120), Agfa Clack (120), and Polaroid SX70. Prices run from $25 to perhaps $100. These are good for landscapes, travel, street photography, and informal-type portraits.

Rangefinder cameras that use 35mm and 120 film can have higher quality lenses and bodies. Their reputation for good images is well-known, and you can get precise with them, but they are trickier to frame your image precisely. They use a general range of focus (often designated by icons on the lens… a mountain, a flower, or a person). Examples are the Contax III (35mm), Argus C3 “Brick” (35mm), Voigtlander Bessa II (120), and Kodak Retina. Prices run from $30 to a few hundred. They are good for landscapes, portraits, travel, and street photography.

TLRs (twin lens-reflex using 120 film) cameras are easily identified by having two lenses and focus is adjusted with a dial on the side. Most of them let you view through a large mirror (looking into the camera from above). Legendary sharpness can be found with the Yashica Mat, Rollei Rolloflex, and Rollicord cameras. These require you to be patient with your focus. They are not quick but, ultimately, produce wonderful images. Prices run from about $150 to about $300. They are good for landscapes, portraits, still lifes, abstracts, and travel photography but not really good for fast action.

Artistic-type cameras using 35mm and 120 film are cameras with reputations for giving results that happen outside of the photographer’s control. However, these “quirks” can be incredibly beautiful and are definitely unique, and often they become the ‘hallmark’ of that particular camera (or family of cameras). This category includes cameras like Soviet cameras, pinhole cameras, and toy cameras. Toy cameras vary widely, not only from camera to camera but from roll to roll! Even so, they have a loyal following. Embrace light leaks, unexpected vignettes, streaky lenses, and other signature quirks that will appear using the Holga, Fujipet and Diana. Soviet cameras have a big reputation for their unpredictable yet (usually) beautiful results, especially when paired with lenses like the Helios. Look for Zenit, Zorki, and Kiev (or the Praktica, an East German version) to find the best ones. Prices run from $30 to $300. They are good for a unique, artistic take on landscapes, portraits, still lifes, street photography, and anything else you can think of to photograph with them.

The 35mm / Precision SLR cameras that use 35mm film give you full and complete control over your image’s sharpness and exposure much like a modern digital camera and also provide access to multiple lenses. Back in the day, these were top-of-the-line brands such as Nikon, Canon, Minolta, Fuji, and Olympus. Excellent quality and great lenses are still easy to find on places like eBay. In this category you can even find many with automatic focusing, in-camera-metering, and more newer technologies than you might expect. I place all Leicas in this category, but they have never been in my price range. Prices will definitely vary here and can go into the high hundreds. They are good for landscapes, portraits, street photography, still lifes, and fast action. In short, they are good for everything you might now currently shoot with a DSLR or mirrorless camera.

Medium Format cameras that use 120 format film include Hasselblad, Bronica, Yashica, Crown Graphic, Mamiya RB67, 645, and the Pentax 645a (which has auto focus!). These cameras require you to take your time but can also deliver really beautiful, ultra-high quality work. Lenses are always excellent, but these cameras sometimes can be tricky when loading film. Prices range from $500 into the thousands of dollars. They are good for landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and abstracts but are not really good for fast action.

Film – The number of films available today and their wide range of effects may be surprising. Many new companies are to be found along with well-known companies who have been producing film for decades. Each film they make has a specialty. Some are ultra-fine-grained while others are entirely grainy. You can find medium contrast and high contrast film and enjoy both ends of the spectrum. The easiest films to use, in terms of availability for purchase and ease of getting them processed, are 35mm and 120 film.

Color films, in general, are usually finer-grained, even in the higher ISO versions, and there are all sorts of tones and color intensity to consider. The classic color films now are by Kodak and (for now) FujiFilm. Kodak has been making film since 1889 and offers versatile films like Kodak Gold (which works well for most everything like landscapes, wildlife, and street scenes, and Kodak Portra which has long been the standard film for portrait and wedding due to its ultra-smooth grain and incredible skin tones. Kodak Ektar, a “slide” film instead of a negative film, has intense, bright colors and rich blacks, reminiscent of the legendary Kodachrome.

FujiFilm, which has been making film since 1934, will soon be gone but for the moment is still available in the US. It offers consistent grain and excellent versatility in their Superia and their Pro films. Their FujiColor 200 may be the most widely available film in the United States. FujiFilm is known for having a “cooler” tonal range that landscape shooters especially love. Provia, Fuji’s transparency or “slide” film, is their top-of-the-line film which renders the highest level of detail and widest range of colors in the Fuji lineup. Fuji’s films also give a clean, “modern” look to images.

Other niche brands with unique looks are the Lomography brand, Dubble, Kono brand films (color with a wide range of creative themes), and Cinestill (intense colors even in low light). Black and white films can offer up traditionally smooth, fine grain, or they can be rich in contrast, with deep darks, moody tones, and a gritty look. Films to try are Kodak (Tmax and TX, consistent soft tones and great range of mid-tones), Fuji Neopan (Acros), AristaEDU, Ilford (HP5 for classic tones and Ortho for gritty high-contrast), Cinestill and Monster (which make high-contrast images reminiscent of early black and white movies).

The Unexpected – This is what I think may be the best part about working with analog films and cameras… So much of what will happen is truly out of the photographer’s control. Depending on which camera you use, your images will take on the “look” that the camera puts on it. This can be anything and everything from strange swirly bokeh (a trademark of old lenses), exaggerated depth of field, edge vignetting, light leaks, and other film-plane weirdness (as with toy cameras). Once you get an idea of the “signatures” your camera makes on your images, you can test out which films you want to pair with that look.

Search engines are a great time saver for deciding which direction to go with for both cameras and film. Many analog photographers have reviews and blogs about their experiences with different cameras and different films. Another excellent source to make use of is Flickr.com which has a search feature and dozens of member groups who love old cameras and who regularly post images. Flickr is a great way to see exactly what that camera’s images will look like, a wonderful way to narrow down your purchase choices before you buy your camera.

The Next Step – After your images are taken, you’ll send your exposed film to a lab for developing and scanning. If you live in a large city, it will be fairly easy to find a local lab to process your film and scan it, otherwise there are national labs with wonderful reputations that specialize in mail-in processing. Scanned images will provide you with JPEG or TIFF files to take into Photoshop or other editing software if you choose to work with them.

If you are only interested in getting your images to Instagram or Facebook, low-resolution scanning will save you money. However, if you are planning on getting prints or canvases made, you’ll need high-resolution scans of your images.

Film Photography Equals Creativity – Film is a great way to expand your knowledge of photography and what it can do, not only in terms of recording a moment but in creative and artistic terms. Film grain just simply looks different than digital pixels. All the variables available with both films and cameras can give you a myriad of ways to express your message and to make a cohesive, signature style that will be all your own. Working with film will make you think more about the image before you take it because you might not get a second or third shot. It is the opposite of shooting digital where dozens of images can be shot in a few seconds and then culled to find your one gem. Many photographers have commented that film makes you slow down when you shoot and appreciate the scene and the creative vibe. Whatever options you choose, remember to view the analog process as a road to creativity and enjoy the view because it really doesn’t matter how you get there!

Lyne Raff is from Lumberton, Texas, near Beaumont, and owns Lyne Raff Photography. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Oklahoma State University and began her professional career as a book and greeting card illustrator and a graphic designer for book publishers. In 2005, she purchased her first digital camera. She admits to being highly influenced by old cameras and historical photographs. She was featured in the March/April 2023 issue of THE PHOTOGRAPHER Magazine. Learn more about Lyne and her work at LyneRaffPhotography.com.

Lyne Raff is from Lumberton, Texas, near Beaumont, and owns Lyne Raff Photography. She has a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Oklahoma State University and began her professional career as a book and greeting card illustrator and a graphic designer for book publishers. In 2005, she purchased her first digital camera. She admits to being highly influenced by old cameras and historical photographs. She was featured in the March/April 2023 issue of THE PHOTOGRAPHER Magazine. Learn more about Lyne and her work at LyneRaffPhotography.com.