To See It, You Must First Understand It

by Mark Bryant

A familiar term used in photography is “See the light.” As important as it is to be able to SEE light, I believe you must first KNOW light. One of my favorite quotes, by George Eastman, is “Light makes photography. Embrace light. Admire it. Love it. But above all, know light. Know it for all you are worth and you will hold the key to photography.”

One of my first recollections of appreciating the beauty of light was on a family road trip when I excitedly pointed out the play of light and shadow on a grassy, rocky ridge to a less-than-impressed audience. I am still on that lifelong quest to replicate the beauty of light that exquisitely comes out of the shadows… to not just see the light, but to know it.

My goal in lighting most portraits, especially sports or character portraits, is not a 3:1 lighting ratio with detail in the shadows. My goal is to create a full range of specular highlights and a long range of midtowns graduating into deep, robust shadows that define and provide a backdrop for the details. My reason for lighting this way was summed up well by Sir Francis Bacon: “In order for the light to shine so brightly, the darkness must be present.”

Renaissance painters, classical portraits, digital composite artists, and even photo enthusiasts snapping photos with their iPhones need light to share their vision with the world. Without light, we cannot illuminate our chosen subjects, and without shadows, we struggle to define or evoke an emotional response from the viewer.

I love and fully embrace the multiple types of lighting: available light, studio lighting, supplemental lighting added to ambient, etc. I own and use studio and location flash modifiers from 5 inch parabolic to 6×8 foot soft boxes, each one having a purpose. The simplicity and beauty of natural light or one light portraiture is quite pleasing to view. Also, multiple light set ups in the hands of a Master Photographer is a thing of beauty.

For some time, I’ve been using multiple lights or a single light and painting details within the scene using both continuous lights and flash. The process is an art form in itself, often called “light painting,” which is most commonly used in still life images. But I also use it for portraits and have found it extremely satisfying and rewarding with results that are hard to capture in traditional lighting.

Obviously, continuous light with portrait subjects is much more difficult, especially with long exposures and darkened environments. But, with patience and a little ingenuity, results can be stunning. Primarily, I use portable flash to light the scene and then add the subject. I love the fact that large, soft light sources and hard direct light can be used together to create eye paths where the viewers visual journey is directed.

By adding this accent light, you will direct light at a greater angle from the camera position than a main light. The greater the angle (incidence), the more reflective, greater intensity, is passed back to the camera lens. The angle of incidence = The angle of reflectance. Also, controlling this accent light is dependent on intensity, size, distance, and how the subject reacts to light by absorption, refraction, reflection, or any combination of these.

Once you begin to know and understand light and its technical aspects, and how to control light, you will have the ability to create exquisite light that brings forth your artistic vision and elevates your work to emotion provoking portrait art.

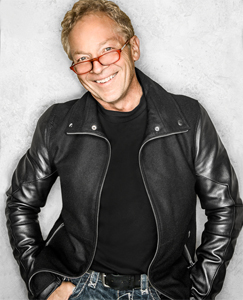

Mark Bryant, of Missoula, Montana, is one of the country’s premier portrait artists.

Mark Bryant, of Missoula, Montana, is one of the country’s premier portrait artists.