by Bill Hedrick

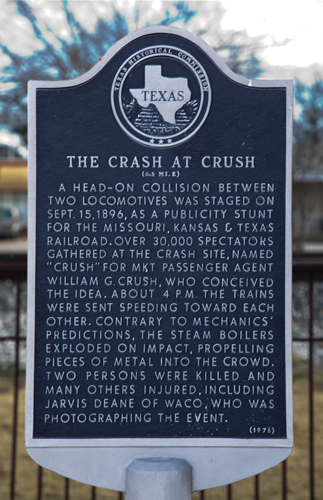

The year was 1896 and the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad, popularly known as “The Katy,” was going through some tough times. The nation was in the midst of an economic depression partly due to railroad overbuilding and shaky financing which resulted in a series of bank failures as well. In response to the sagging economy and the competition in the industry, a ticket agent named William George Crush devised a plan to create a renewed interest in the railroad and to boost ticket sales.

Crush was a keen observer of human nature and noticed that people of the time had a morbid fascination with train wrecks. So, he proposed a plan to stage a head-on collision between two locomotives and invite the public to witness the event!

Railroad officials were skeptical but eventually gave the nod to Crush who went to work on the idea. All he needed from “The Katy” were two obsolete locomotives and a few stock cars. The main requirement was that each one be able to attain a speed of 60 miles per hour. The location for the “disaster” would be just north of Waco, a few miles south of the town of West, and it would take place on September 15, 1896.

It didn’t take long for the news media to pick up on the plan and an estimated 40,000 people showed up to view the spectacle, many of whom had purchased tickets on “The Katy” and arrived from all over the state. The location was given the “temporary” town name of Crush in honor of the promoter.

In preparation for the crash, a 500 man crew had constructed a four-mile spur and piped water from two water wells as well as five tank cars to supply drinking water for the spectators. Grandstands were built, press platforms were in place, and there was even a carnival midway.

The plan called for each of two locomotives to have a one mile “head start” and for each engineer to throw their throttles wide open and then jump clear and let physics take care of the rest. Experts assured Crush and “The Katy” that the two locomotives would not explode but would “jackknife” upwards and come crashing down again. Even so, spectators were kept a good 200 yards away from the site of the collision.

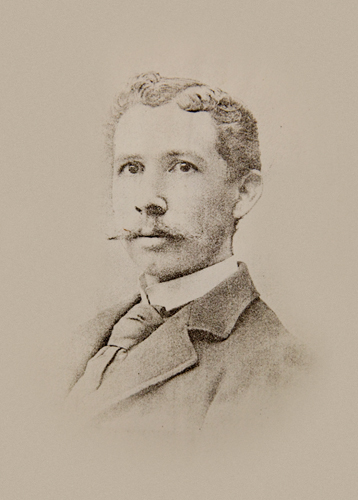

The only exception was a special platform built much closer to the track where a Waco photographer named Jarvis Deane would capture the event on film with several cameras placed at precise intervals and strategic locations. Little did he realize what was in store for him.

The only exception was a special platform built much closer to the track where a Waco photographer named Jarvis Deane would capture the event on film with several cameras placed at precise intervals and strategic locations. Little did he realize what was in store for him.

Two aging locomotives, No. 999 and No. 1001, were selected for the event and had been painted in festive green and red. The six stock cars pulled by each one were adorned with banners for the Ringling Brothers Circus, the Texas State Fair, and even the Oriental Hotel in Dallas, and each had completed whistle-stop tours throughout the state. (continued on page 42)

The event had been scheduled for 4pm that afternoon but passenger trains were still delivering carloads of spectators and Crush announced a one hour postponement. Then, at 5pm, both locomotives steamed slowly down the track and stopped face-to-face in the middle for a “salute.” Then, they both backed to their respective starting points. As Crush raised his hat, the crowd roared and the trains started down the hill toward one another. Crews had fastened “track torpedoes” (small charges used as warning signals) at strategic points along the tracks to add to the drama.

Onlookers had only seconds to absorb what happened next because Crush and his team of experts had predicted that the locomotives would “rise together in an inverted V” while the cars behind them would crumple like an accordion. Instead, the two locomotives “telescoped” into one another and the boilers exploded, hurling “flying missiles of iron and steel, varying in size from a postage stamp to a half a driving wheel” as thousands of people scrambled to avoid the flying debris that was hurled as far as 300 yards… well past the platform where Waco photographer, Jarvis Dean, was positioned.

Several people were killed and others injured and Jarvis Deane lost his right eye and remained in a coma for several months following the event but eventually recovered and returned to his studio. The railroad settled all claims and Deane himself received a $10,000 settlement and a lifetime pass on The Katy.

In the years to follow, Ragtime composer, Scott Joplin, who may have actually witnessed the event, wrote the “Great Crush Collision March” which included instructions in the score for replicating the sounds of the collision through playing techniques, special notes, and the use of dynamics.

Then, in 2007, playwright, Jo Morello, came to Waco to research the event and wrote the play “The Crash at Crush” which was produced in Dallas the following year. She was, in fact, instrumental in obtaining rare photos and details of the event for this article.

Upon returning to work, Jarvis Deane posted a notice in the Waco newspapers stating, “Having gotten all of the loose screws and other hardware out of my head, am now ready for all photographic business.”

Upon returning to work, Jarvis Deane posted a notice in the Waco newspapers stating, “Having gotten all of the loose screws and other hardware out of my head, am now ready for all photographic business.”

Just two years after the “Crash at Crush,” in 1898, Jarvis Deane became the first President of the newly organized Texas Professional Photographers Association. As Paul Harvey used to say, “…and now you know the rest of the story.”