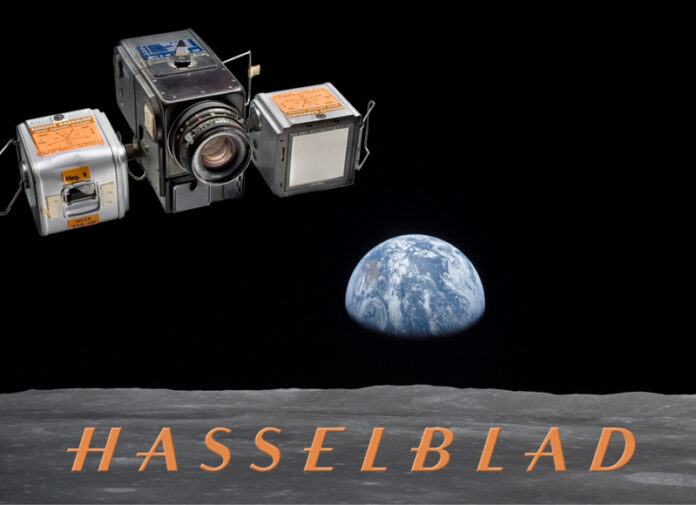

“Earthrise” (above) was first witnessed by Apollo 8 astronaut Bill Anders. The modified Hasselblad 500C camera (left) shed its viewfinder, reflex mirror, auxiliary shutter, and even the leather cover to minimize the camera’s weight impact on NASA missions.

By Bill Hedrick

Dedicated to the memory of William A. Anders (17 October 1933 – 7 June 2024).

It happened just after 10:30 am Houston time on December 24, 1968, as Apollo 8 astronauts Jim Lovell, Frank Borman, and Bill Anders were coming around the far side of the Moon for the fourth time. Mission Commander Frank Borman was in the left seat preparing to turn the spacecraft to a new orientation, according to the flight plan. Navigator Jim Lovell was in the lower equipment bay about to make sightings on lunar landmarks with the onboard sextant, and Bill Anders was observing the moon through his side window and taking pictures with a Hasselblad still camera fitted with a 250mm lens.

Meanwhile, a second Hasselblad with an 80mm lens was mounted in Borman’s front-facing “rendezvous” window, photographing the lunar surface using an automatic timer that took a new picture every twenty seconds. Suddenly, Bill Anders interrupted the conversation, “Oh, my God! Look at that picture over there! There’s the Earth comin’ up. Wow, is that pretty!” Because he was shooting with black-and-white film, he asked Jim Lovell to hand him a color film magazine.

There was a sense of urgency in his voice, “You got a color film, Jim? Hand me a roll of color, quick, would you? Hurry.” The result was the iconic “Earthrise” image of a colorful Earth rising over the harsh and bleak lunar landscape. For those who first saw it, Earthrise was an unexpected and electrifying experience and an iconic image of the 20th century. It was also one of Hasselblad’s proudest achievements as part of space exploration history.

The Hasselblad 500C that initiated a relationship between the camera company and NASA several years before the launch of Apollo was a technologically advanced camera at the time with a leaf shutter and automatic aperture stop down. Wally Schirra, a NASA mission pilot and photo enthusiast, suggested the 500C, a camera he already owned, be adapted to document human space travel. Seven years before the first Hasselblad would drop to the dusty lunar surface, NASA and the Swedish camera company worked together to modify cameras for the extremes of space.

The camera shed its viewfinder, reflex mirror, auxiliary shutter, and even the leather cover to minimize the camera’s weight impact on the mission. The modified 500C then gained a 70-exposure film magazine instead of the traditional dozen photographs in a single roll. The retrofitted camera was taken aboard the Mercury 8 in 1962, taking photographs while orbiting Earth and paving the way for Hasselblad’s first trip to the moon.

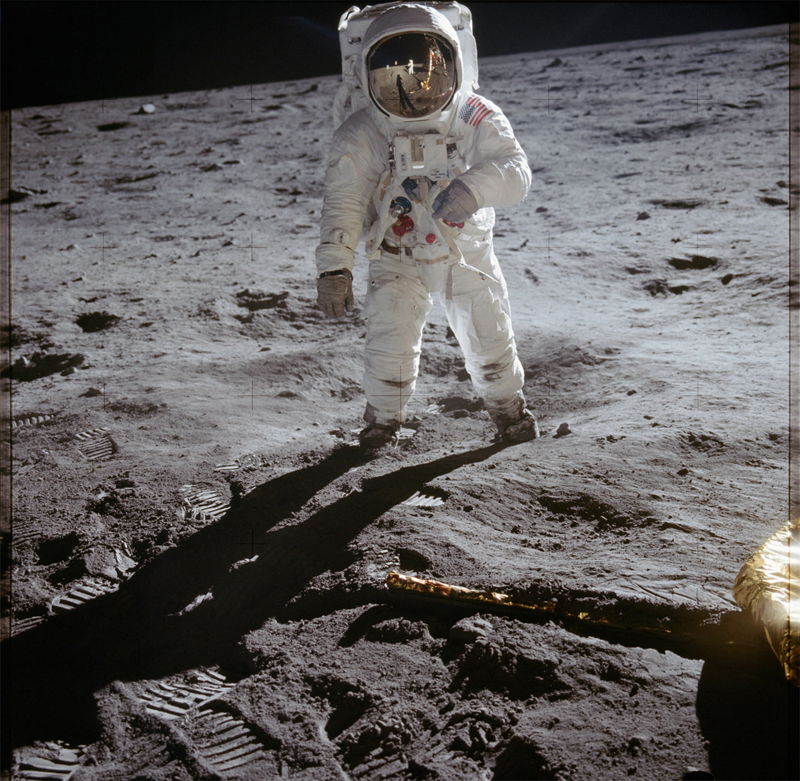

By the time Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the Moon, Apollo 11 was equipped with three of the medium-format cameras, including the Hasselblad 500EL Data Camera (HDC) and the Hasselblad Electric Camera (HEC). The first was outfitted with a Zeiss Biogon 60mm f5.6 lens and a specially-designed film magazine that allowed for 200 exposures on Kodak 70mm film. The second camera used an 80mm f2.8 lens to capture images from inside the Eagle lunar module, and a third camera was used inside the Command Module with crew member Michael Collins while his two crewmates were on the lunar surface.

Like the 500C on earlier missions, the HDC camera was adapted to withstand the rigors of space, using silver paint to help the camera move between -85 degrees and 248 degrees Fahrenheit. A special plate was added to the camera to intentionally leave “+” marks in the images, which would later be used to make measurements and gather more data from the images.

Basic photography principals, as well as instructions on using specific Hasselblad cameras, were built into NASA’s training program. As Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin ventured outside of the Eagle lander, Armstrong captured the first “selfie” when his own image was photographed as it was reflected in Aldrin’s helmet visor.

When Apollo 11 blasted off from the Moon for the return trip to Earth, the American flag was not the only thing that was left behind. Sadly, after successfully capturing images on the lunar surface on July 21, 1969, the two Hasselblad cameras were left on the Moon. After they were hoisted up using a line to the lunar lander, the valuable film magazines were removed from the cameras. After an eight-day journey, the spacecraft that weighted more than 100,000 pounds at launch would return with a landing mass of less than 11,000 pounds. To cut weight for the return journey, the cameras and lenses had to be left behind on the Moon where they remain to this day, along with 10 others from later missions.

Those of us who used Hasselblad cameras in the decades since Apollo and before the digital revolution remember it as a dependable workhorse that set us apart from everyone else. The space program catapulted it into world fame and those of us who depended on it for our livelihood will never forget the vital role it played in the history of the world.