by Bill Hedrick

For generations, professional photographers have been making restored copies of old and damaged photographs or paintings. Some of us even recall the days before digital imaging when photographic artists used a variety of methods, including airbrush and other media, to produce them. Of course, when Adobe Photoshop came along, the process became much easier and, today, just about anyone with a working knowledge of Photoshop can do remarkable things with a digitized image. But Julian Baumgartner actually restores original pieces of art.

Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration was founded in 1978 on the north side of Chicago, Illinois, by R. Agass Baumgartner. He was born in Switzerland and attended the Luzern Academy of Art and the École des Beaux-arts in Epinal, France, majoring in studio art and art history. For eight years, he apprenticed and worked in the department of art conservation at the Museum of Art and History in Fribourg, Switzerland. During that time, he freelanced in mural and 16th through 19th century easel painting restoration and conservation. Until his passing in 2011, his son, Julian, worked by his father’s side, mastering the processes of fine art conservation and restoration.

Julian’s philosophy, like that of his father, is to alter the artwork as little as possible with respect to the original intention of the artist. To that end, they examine each work of art closely and tailor their methodologies to meet both the needs of the painting and the client.

What makes this process so unique and so foreign from the process traditionally used by professional photographers is that the work is done on the original image. That is correct. Julian Baumgartner boldly goes where no photographer would dare… and does it routinely. His secret advantage is that his process is noninvasive and fully reversible.

“All of the materials we use are fully reversible, PH neutral, and specifically designed for conservation. The artwork is conducted in accordance with modern conservation practices and under UV light and can be easily removed,” Julian explains.

Because each job is different and unique, the first step is to view the artworks preferably in the studio with the clients. If that is not possible, photos can be emailed or uploaded and, if circumstances demand, an on-site consultation can be scheduled. Once received, a full examination of the artworks is performed. This will include assessing the condition of the artwork and testing of the materials that will guide the conservation process. Only then can a proposal be made for the client. “The proposal will contain a time line and price,” he explains. “At no point will the price ever change. What is quoted is firm and will never increase midway through the process, regardless of any complications.”

It is not uncommon for the attributions of a painting to be lost as it passes through various hands. Sometimes identifying a painting is quite simple and a catalogue raisonné can be consulted for confirmation. Other times, often when the work has no provenance or is otherwise in doubt, the conservator can provide invaluable resources and expertise. BFAR has provided access to research materials and scientific analysis to all clients and, as a result, have come through with discoveries of otherwise unknown artwork.

One client purchased a painting, “Young Fisherman, Hudson River Palisades,” at an auction and it sat for several years. With no signature and no provenance, the artist remained a mystery. Through extensive research, the owner had narrowed the possible artist but had come to an impasse because no history of the work existed. After an examination that included ultraviolet and infrared photography, BFAR discovered the remnants of a previous sketch. Although it was invisible to the naked eye, it was an exact match to a page from the sketchbook of George Caleb Bingham, a noted Hudson River School painter. Working with the owner and the author of the catalogue raisonné, the painting received legitimate attribution, a working title, and inclusion in the next printing of the raisonné.

There have been several discoveries like this, according to Julian. In another case, a painting arrived in very bad condition. It had been poorly wax-lined and so thoroughly over painted that little of the original sky was present. His first goal was to undo all of the previous work and bring the painting back to the artist’s original intent. That process revealed previously obfuscated areas of the image that had been over painted. In addition, when the old lining was removed, faint markings were found on the canvas. Utilizing infrared photography, the remnants of an ink inscription were revealed to be a signature, title, and description of one of the seminal moments in early American history: the storming by Native Americans of Fort Dearborn on Lake Michigan’s Shore.

So, what does a typical job involve? Because each assignment is unique, Julian uses a variety of methods for the conservation process. An example would be a restoration of a painting of “Mother Mary.” According to Julian, “This image had severe damage due to moisture, resulting in a lot of flaking, punctures, and tears. It was dirty, had an old varnish coating, and had a lot of paint missing in places.”

Step one of the process was to remove the painting from the stretcher, being careful to preserve the tacking edge. After cleaning the back to get rid of dust trapped between the stretcher bar and canvas, the task of repairing tears, called “Bridging” begins on the back of the canvas. Using little strands of Belgian Linen, Julian uses conservation adhesive and lays the strands perpendicular across the tear to provide stability so the tear does not move. This also provides a foundation for the filling medium which will replace the missing pigment.

Next, Julian addresses the tack edges of the canvas. Strips of Belgian Linen are cut and one edge frayed to be used over the old tack edges, a process called “Strip Lining.” Using a conservation adhesive film (iron-on), these strips cover the old ones, providing a new and stronger surface for re-stretching the canvas on the frame.

With the back of the image done, it is time to clean the painting. Most paintings have varying degrees of surface grime, consisting of dust, dirt, and oil on its surface. That layer of grime prevents the solvent from penetrating, so Julian must clean the surface using a special mixture of paste. He works slowly and in isolated areas at a time. Once that is done, the canvas can be re-mounted to the frame and it is ready for restoration.

Now the hard work begins! Every place where there is missing pigment or a tear in the canvas, a special putty is used to fill in the depression. Unless this is done correctly, each place will show up after the final work is completed. Once that is accomplished, he uses conservation pigment and mixes colors, slowly adding them as needed where colors are missing. “As a conservative, my job is to restore the painting as the artist envisioned it and not to make editorial decisions,” he explains.

“Some days I have to wipe it all off and start all over because the lighting wasn’t right or because I wasn’t satisfied with the retouching. But the good thing about using archival and reversible pigment is that I can remove my retouching with damaging the artwork.

“Some days I have to wipe it all off and start all over because the lighting wasn’t right or because I wasn’t satisfied with the retouching. But the good thing about using archival and reversible pigment is that I can remove my retouching with damaging the artwork.

With all of that done, the painting can be varnished, using a combination of matte and gloss varnish with a UV stabilizer to help prevent the varnish from yellowing. “I prefer to brush it on the painting as opposed to spraying it on because it gives me a little bit more control.”

In the Photoshop age, it’s easy to think that a few simple mouse clicks is all it takes to completely edit or fix an image. But it’s a different world when you’re dealing with precious pieces of art that are worth thousands or possibly millions of dollars. Making these masterpieces look like new again without botching the job is not for the faint of heart and requires a highly trained hand. Even though the process is “fully reversible,” Baumgartner Restoration insures their clients’ work for up to $500,000 and more.

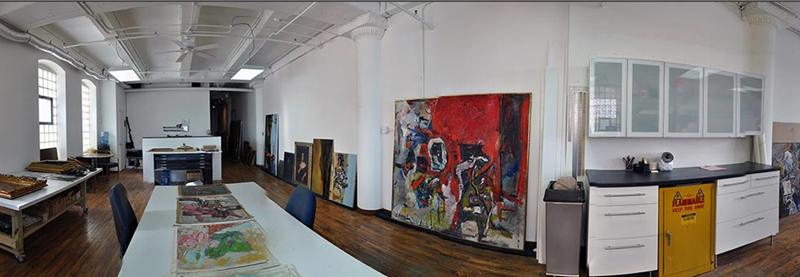

There are other conservation studios and many of them have grown exponentially. But Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration made a decision years ago to stay small. “Clients can be sure that their artworks will only ever be touched by one set of hands,” he explains. It is part of a tradition started by his father who believed that, by fostering a personal relationship with every client, the best results can be achieved.

You can learn more about Julian Baumgartner and this incredible process at their website: www.BaumgartnerFineArtRestoration.com. You can also view a more detailed video of the restoration of the painting of “Mother Mary” on youtube.